Part Two: Of the Defenses

Chapter 1: Of the Common Guard and Movements of the Arm and

49. Considering that defense is the most useful of skills I should treat of it before offense, but without first giving at least an idea of the form of the simpler attacks, we would lack cases for applying the defenses, and examples of its practice, I must begin with the movements of the arm and sword, of the agile wrist, and those which I call formations.

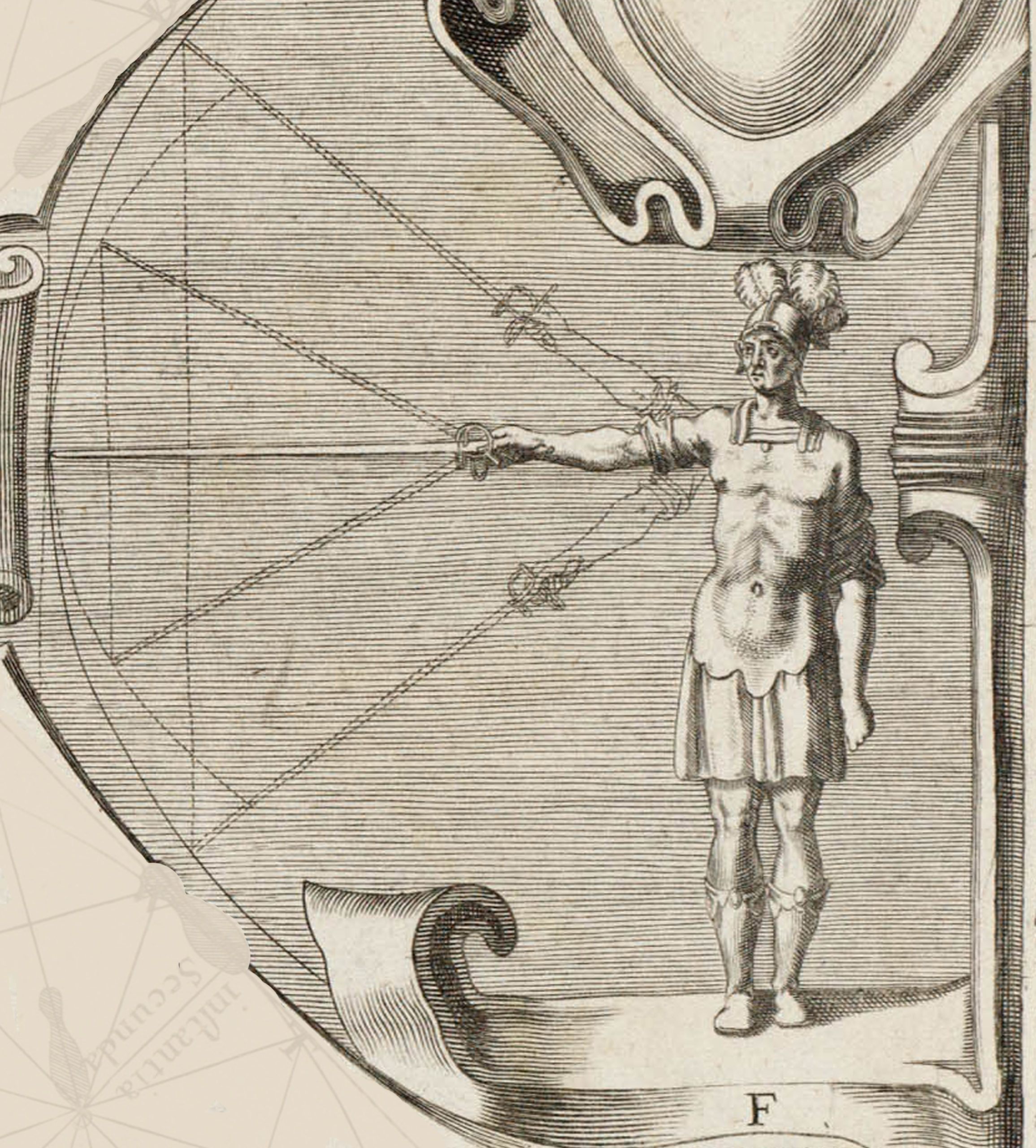

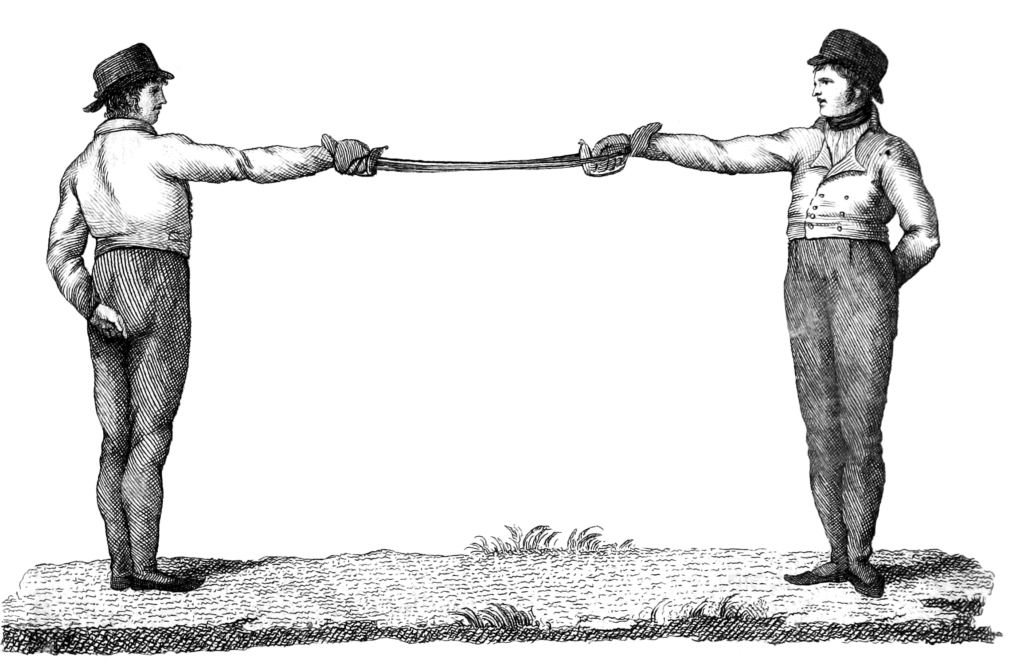

Finding Initial Measure

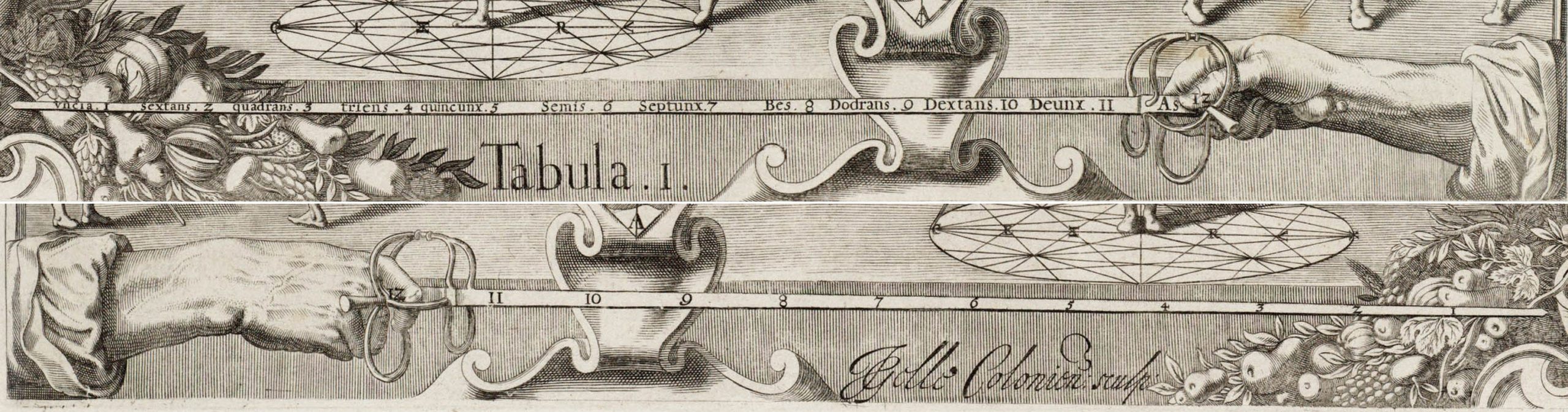

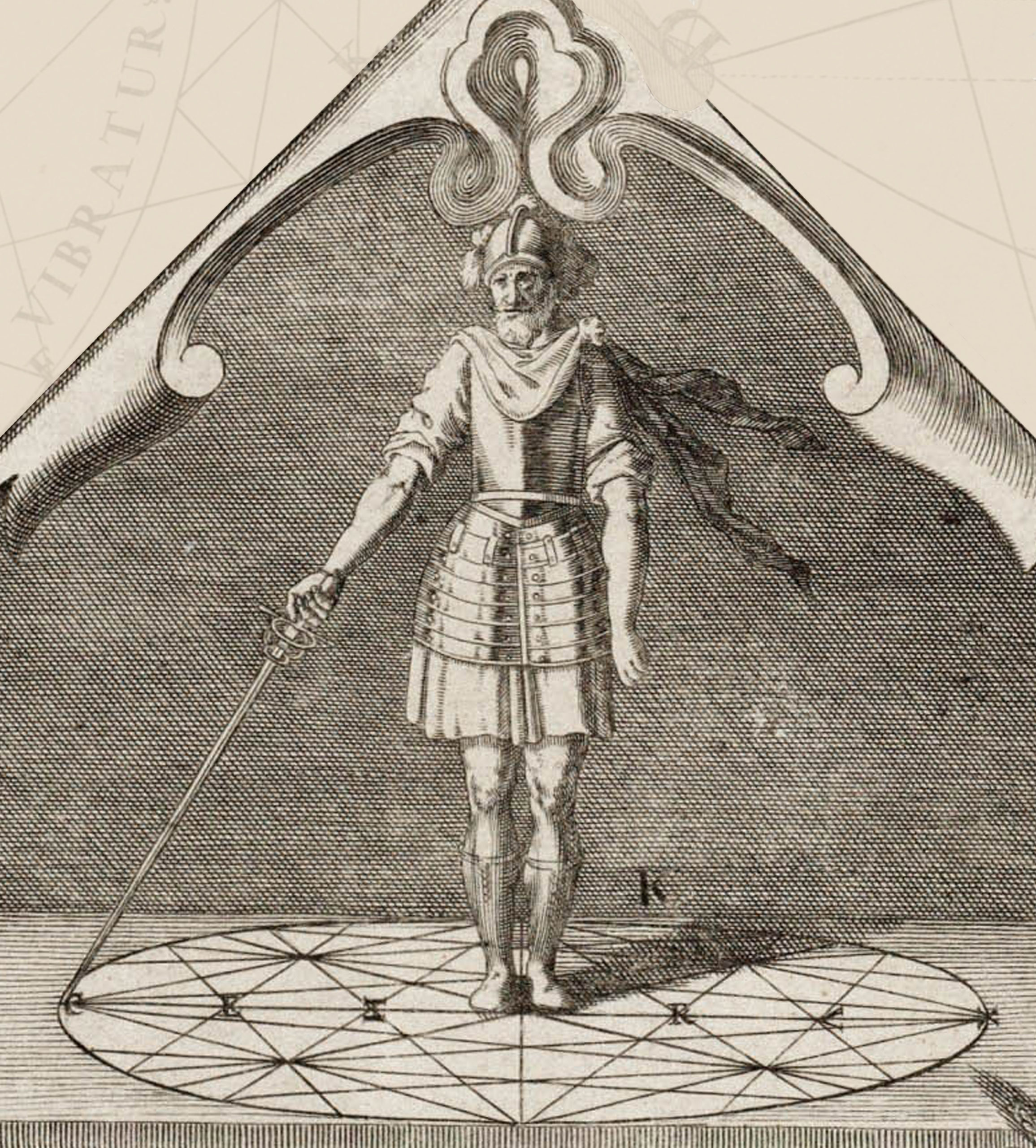

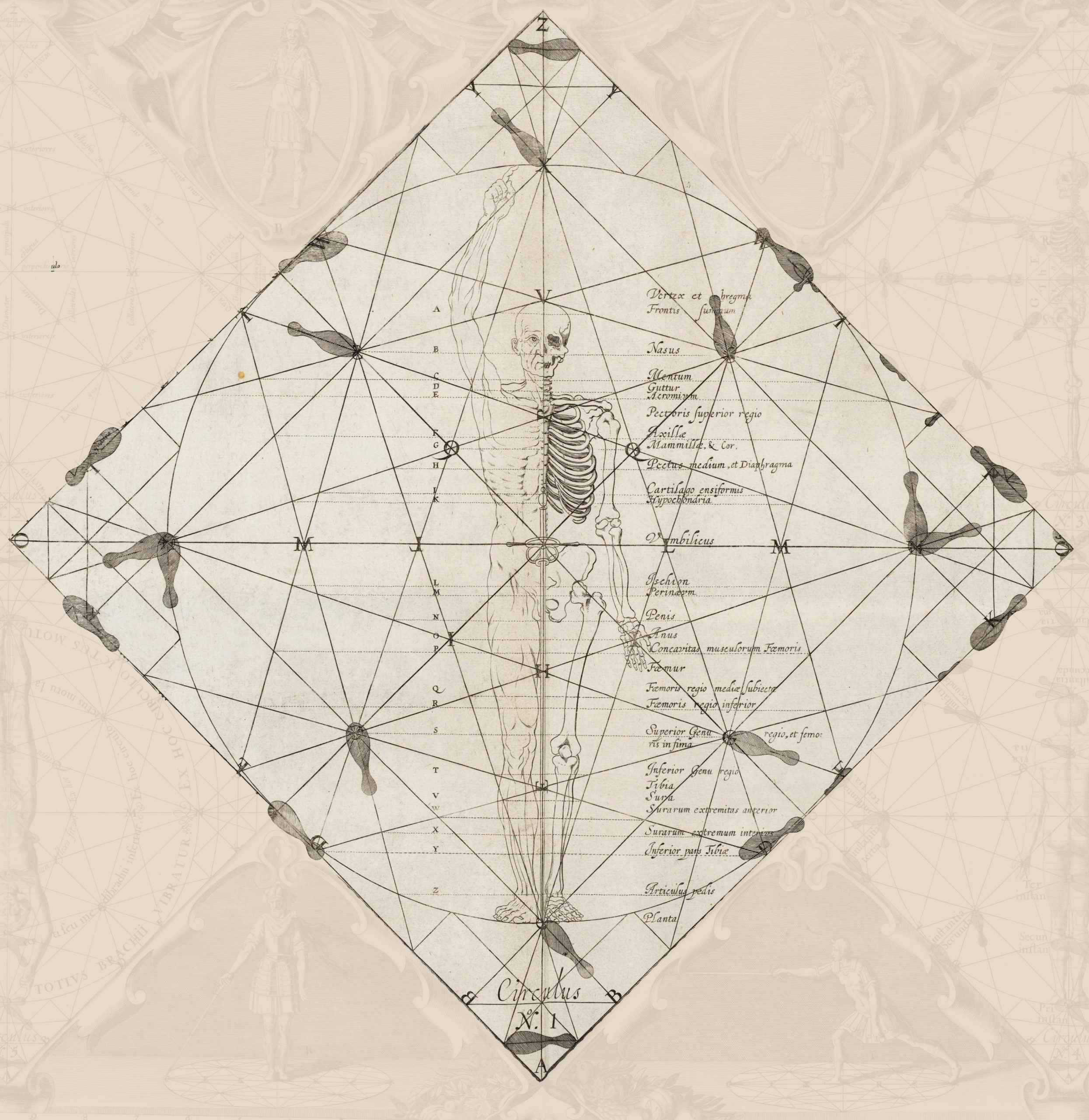

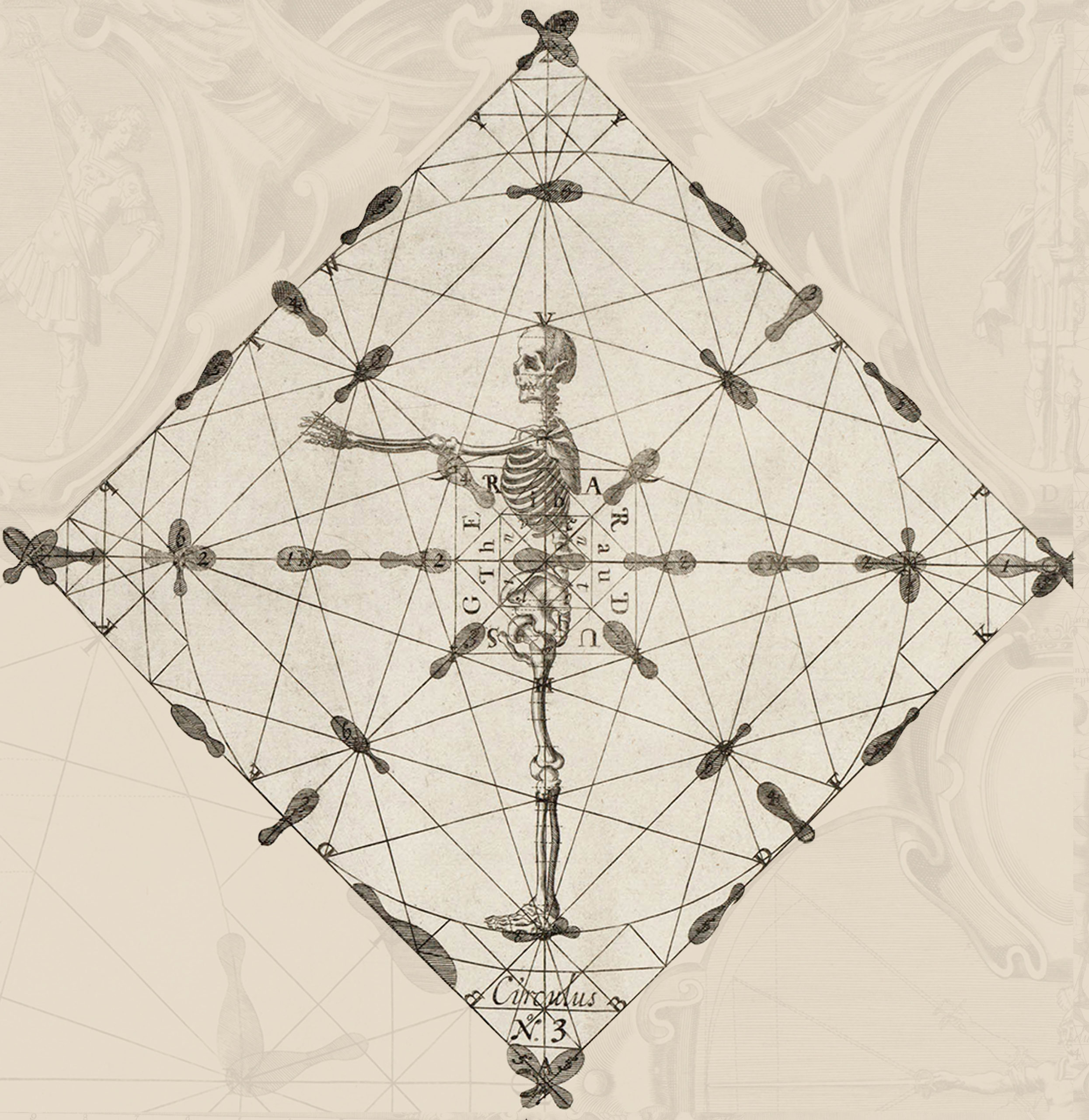

50. To begin the material of this part, nothing comes before choosing the distance which one must stay from their opponent; Therefore, if you are each in the right stance, hold the sabers with arms fully extended so that they make a straight line from the shoulder to the right hand and the points of the sabers touch the shells (lamina 3. Figure 4.). This distance, which we call proportion (defensive) is represented in lamina 2, letters A.Q.

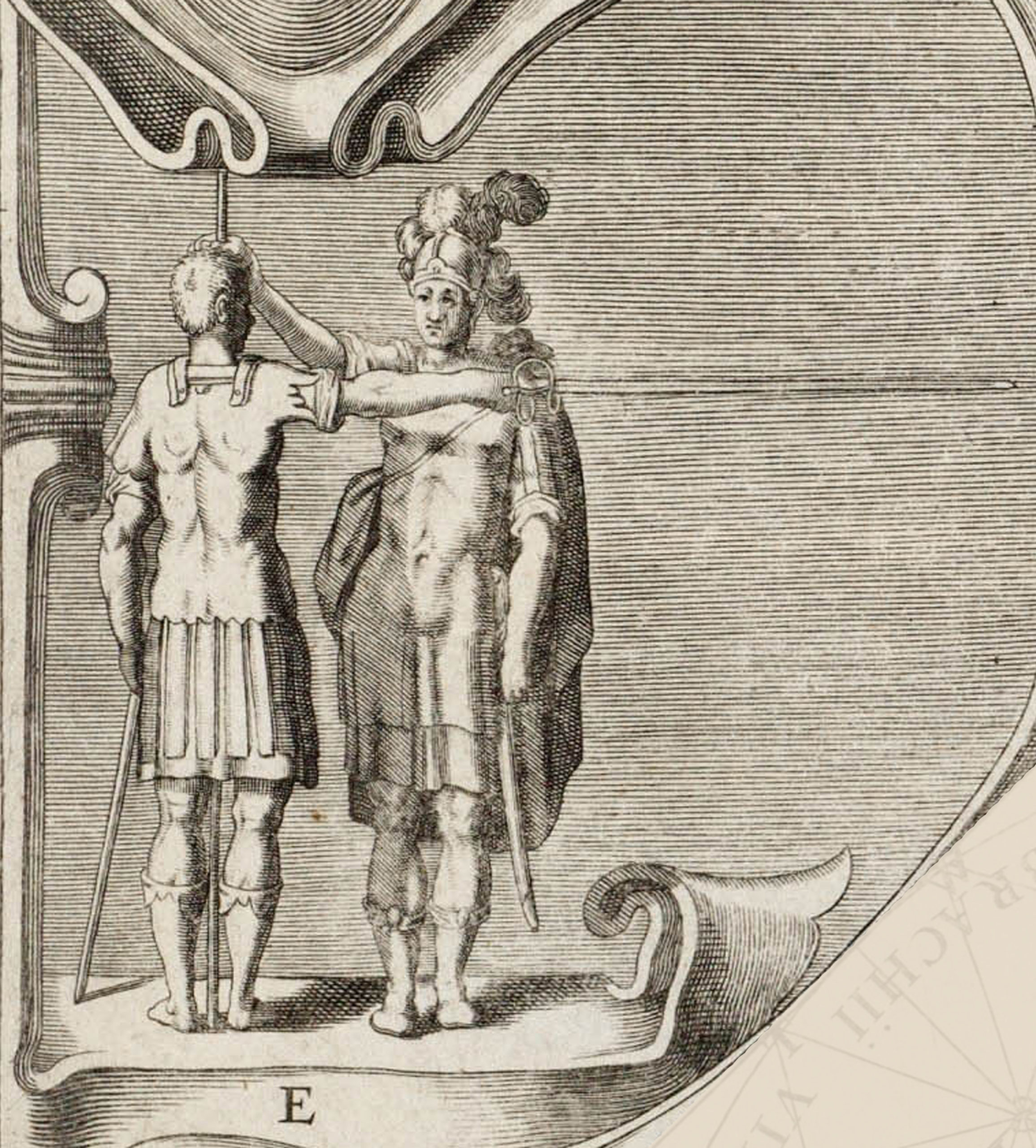

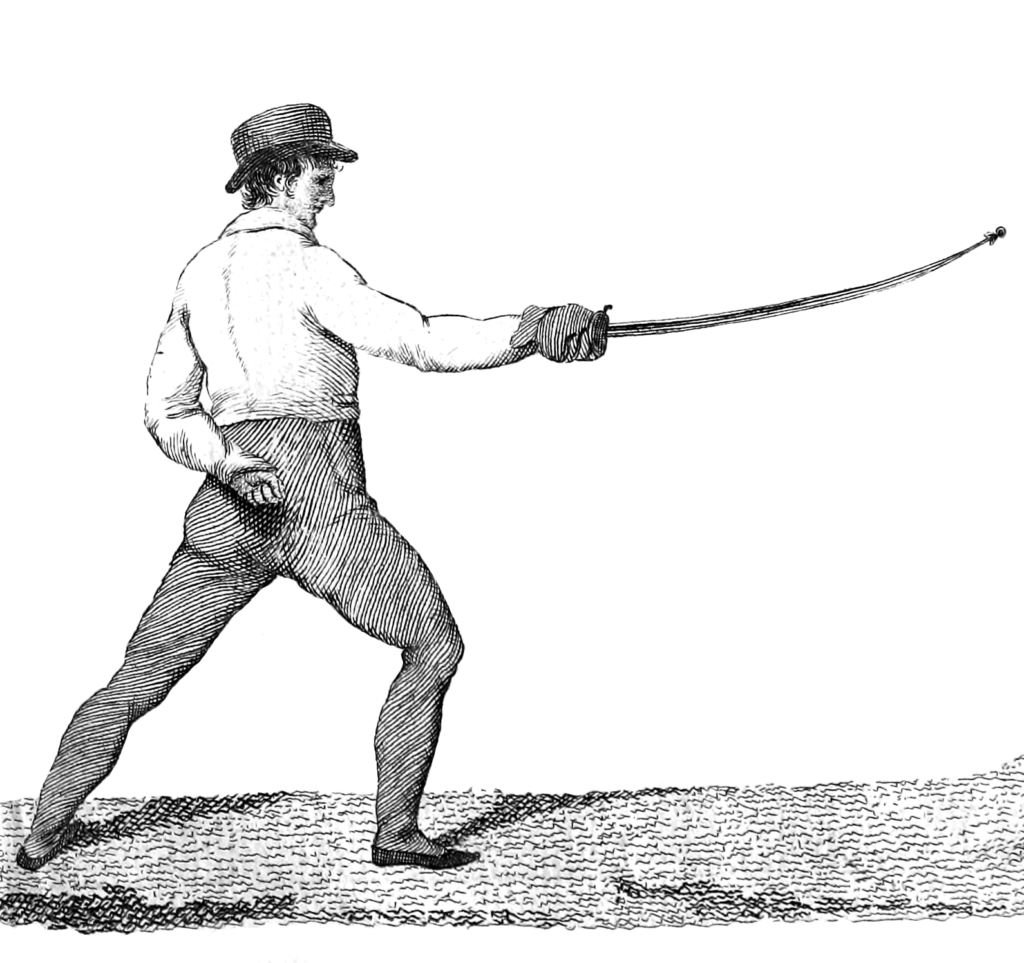

The Common Guard

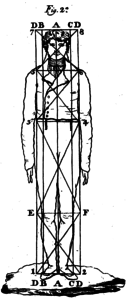

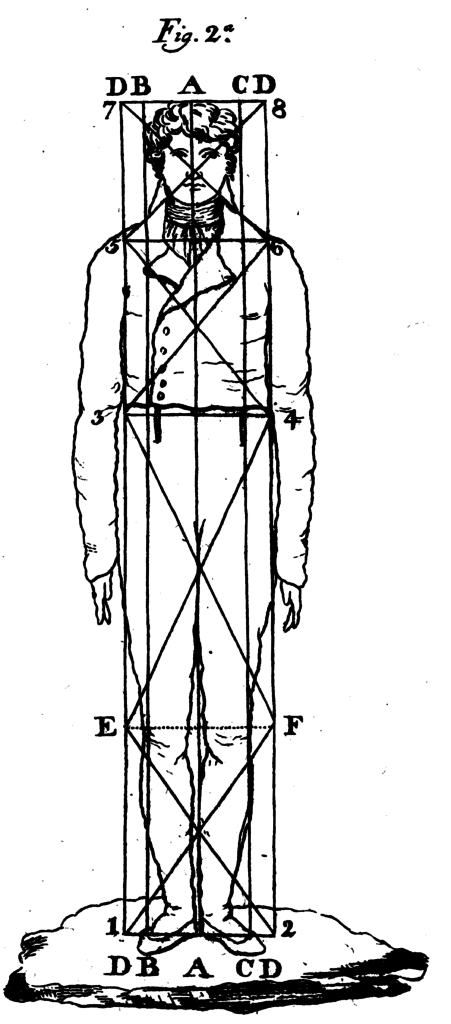

51. To finish this movement we call choosing the distance, step first to assert the offensive stance (§36) with the arm slightly bent, the hand perfectly covering the grip and the thumb and index finger playing a little on the shell: The guard at the height of the median plane (Lam. 1, fig 2, numbers 3 & 4); the point at the height of the opponent’s mouth, the cutting edge directed toward the ground and the left hand held back so it is protected from the cuts of your own saber or that of your opponent; all of this is represented in fig. 5, let. A, lam. 3; this skill is called asserting the common guard in the stated stance.

Lam. 3, Fig. 5, B: Defensive Stance

52. If your contrary takes the position explained, assume the same guard in the waiting stance (§36, and fig 5, letter B). What we call the Inside is understood to be everything from the right shoulder to the left in the front, and what is from shoulder to shoulder in the back is called outside: this is without the weapon, it is affirmed in part, that which is to the left of the shoulder is to the inside, that which is to the right is the outside. The part that guards the head is called high, that which guards below is called low.

Positions of the hand

53. For the good formation of attacks and removals it is necessary to know the phrases that I will use in this doctrine. I call it Third Position when the armed hand is held low, palm facing down with the blade of the sword horizontal and the edge to the right. Fourth position is where the hand is placed palm up or looking at the sky, and the saber blade is held horizontally with the edge to the left. When, in any of these positions, the hand turns so that the blade does not become horizontal or perpendicular to the common guard and it is not between one or the other, it is called half position in Third or Fourth. These positions combined with the formations that I will put below form the defensive part, therefore I will trust in the steadfastness of repeating them many times.

Methods of Freeing the Blade

54. When you have to form any free offense, it is necessary that the weak of your sabre be dominated by the strong of your opponent’s; since freeing it is nothing other than removing the weapon from that domination, which is done either passing the point from one side to the other from below, or above the enemy’s guard, or by removing the point. The first and second of these operations precede all of the thrusts and some of the cutting blows: the last always goes to the cut.

Frias is introducing a concept here that is very important to understanding both the attacks given below and his later discussions of exposure in the guards. In his usage, a blade can either be “free” or “aggregated.” A blade is “aggregated” when it is in contact with the opponent’s blade and “free” when it is not. Freeing the blade, is the act of removing it from an unfavorable aggregation, and the distinction Frias is making here is in the type of arrangement that one uses to accomplish that. If your blade remains in a point forward orientation, more or less directed at the enemy, you are freeing by the guard (think of the circle disengage we see with modern fencing and rapier as an example of this arrangement). If your blade is withdrawn toward the opponent’s point, so that your point is required to move offline in order to free the blade, you are freeing by the point.

55. It should not be understood by virtue of these notices, that I am going to treat upon the execution of attacks, as this chapter has no other object than the agility of the arm for the good teaching of defense, less will be done regarding all of the offenses, the lunge or choosing the defensive measure, essential circumstances for the execution, these I defer for the third part of this treatise. This course shall begin with the formation of cuts.

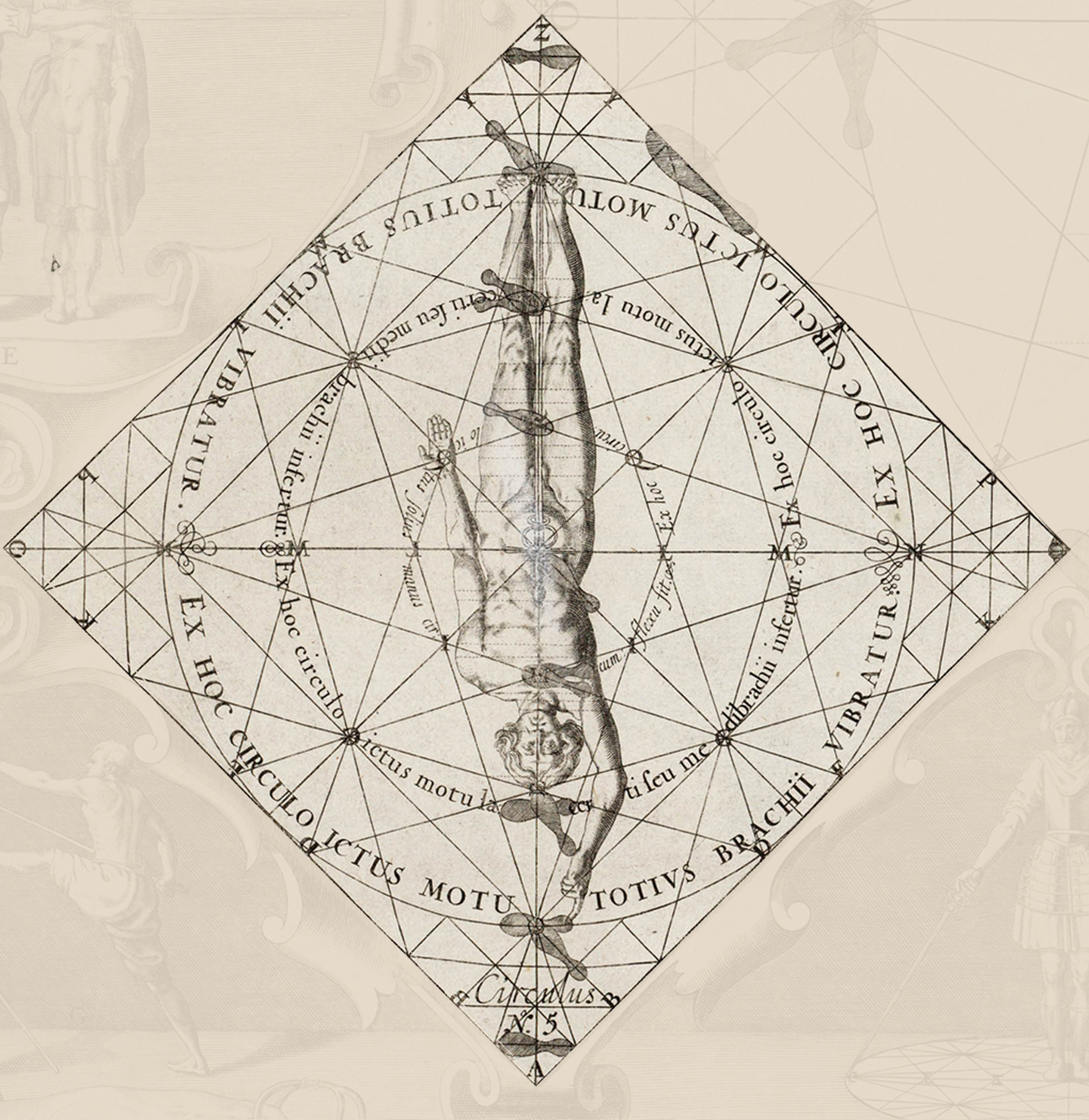

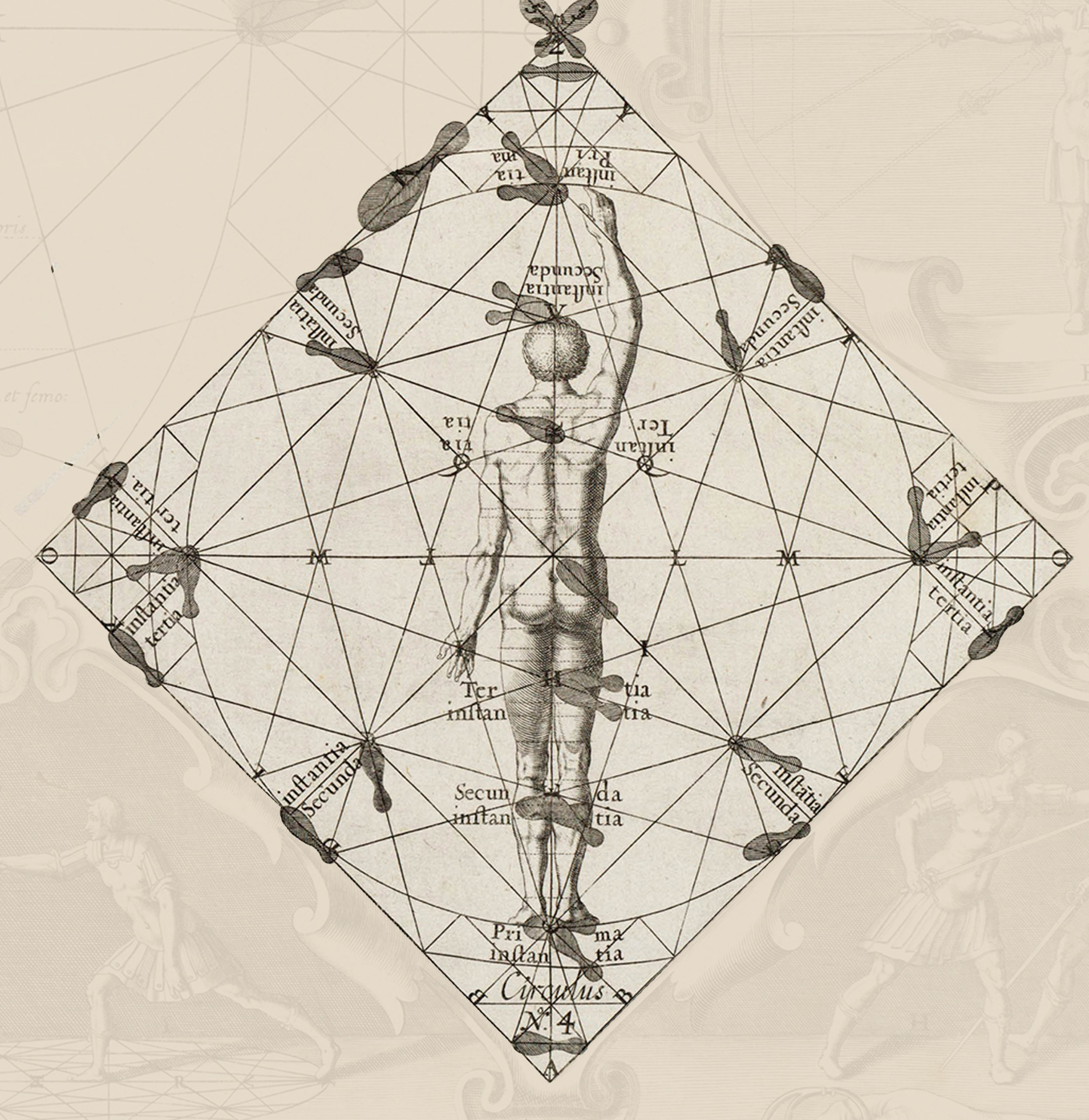

Movements of Formation and Movements of Execution

56. All of the wounds, whether cutting or thrusting are divided into formation and execution: I call formation the movement which is done with the sword, from any guard or position to put it in a disposition to direct it to the point we are trying to hurt. The formation is complete when the sabre, to reach the attack-able place does not require more than a straight line for the thrust and cuts without any obstacle; whose path constitutes the execution.

Free Diagonal Cut

57. Position in the common guard and the stance for the attack, add the enemy sabre on its outside part, turn the hand to the half-third position and bend the arm sufficiently by the point of the opposing sabre, making it pass in front of your face, raise the guard to the height of the superior plane, up to the line with the right shoulder, and in the position of half-fourth. Extending the arm from here without lowering the guard and facing with the edge the direction of the diagonal 8, 5. plate 1. figure 2., execute a diagonal cut. Freeing your sabre by the point from the other, until the guard is in front of the shoulder, we call formation, and from here to the end of the movement to cut, execution. Note that in any cutting wound the sabre passes in the execution of the point where the lines terminate.

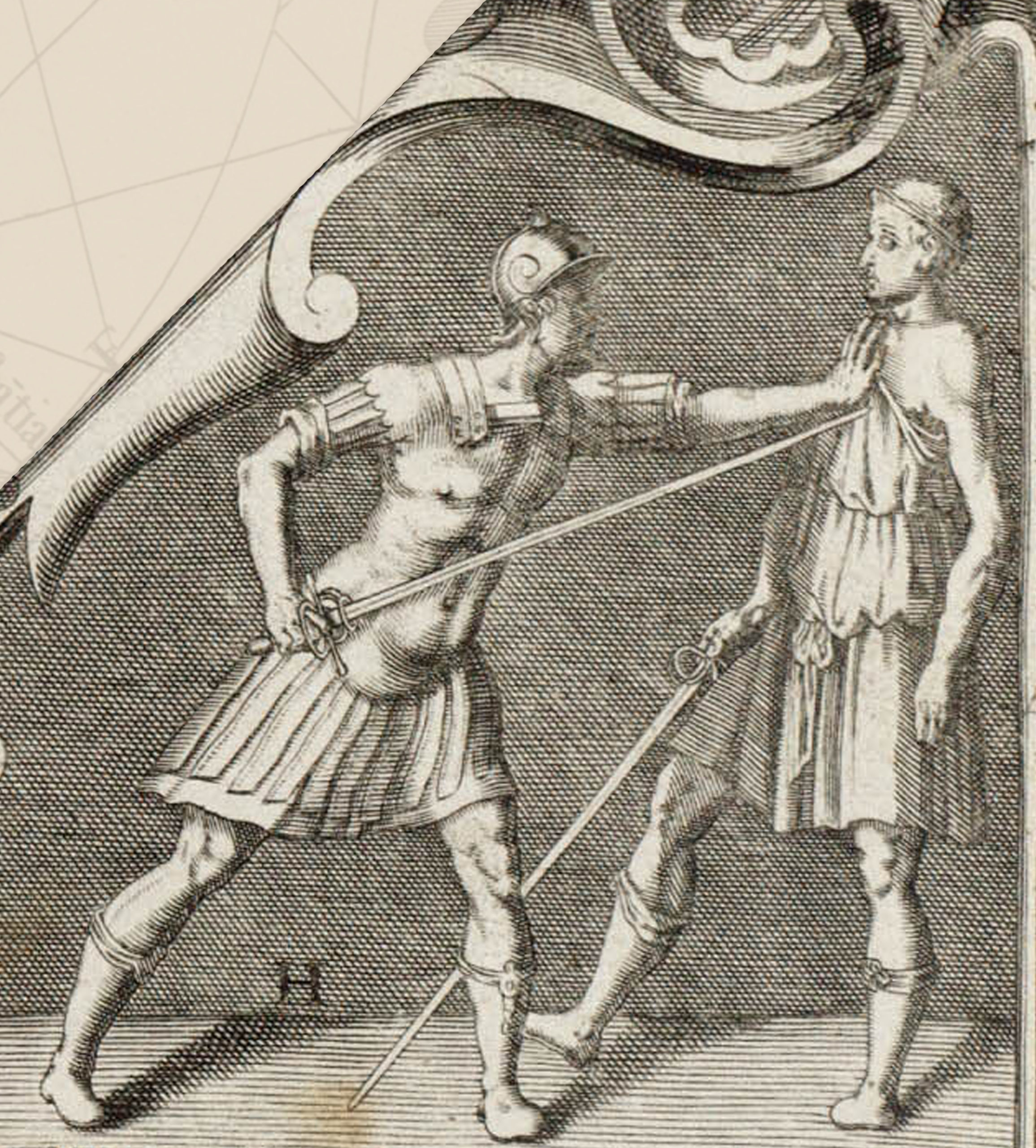

Free Diagonal Reverse Cut

58. When the two combatants are in the common guard and the enemy adds his sabre to the inside line, then turn the hand in half-fourth position and bend the arm the precise amount to release the point of your own sabre from the other, take it in front of the face until it is in front of the left shoulder, with the guard at the height of the superior plane in third position so that the edge of the weapon looks at the right diagonal of the face of the enemy (plate 1, figure 2, numbers 7.6) and from here, extend the arm with the hand in the position of half-third as said, and forming a straight line from the point of your sabre, and the place of the wound with the guard and the right shoulder, you will execute a diagonal reverse to the face. The vertical cuts and reverses differ from the previous ones in that to guide the vertical A, it is necessary when in the execution to keep the sabre with the edge directed toward the ground when in the guard position.

General Rule Regarding Movements to Profile or Square

59. Note that all of the attacks executed from the inside line of the enemy must be accompanied by the motion to profile, and those executed from the outside, with the motion to square; more, all of The wounds of the edge, which form from the outside are called cuts and those executed from the inside are called reverses.

General Rule Regarding Order of Operations in Movements of Formation

60. Take note that for the formation of all of the attacks, immediately begin by taking the guard to the height of the shoulder, whether it is to wound with the cut or with the point. In the execution, be careful that the guard is at the height of the mouth in all the attacks directed to the points comprising the distance from the nipples to the supreme plane; and those heading from the nipple to the lowest plane, they must form a straight line with the the shoulder, arm and sabre to the point of the injury.

Diagonal Cuts and Reverses to the Body or Thigh

61. All of the formations that follow are also begun from the common guard. The diagonal cut to the side is formed as described in the treatment of the diagonal to the face, with only one difference that their execution will be on the line 6.3, plate I, figure 2 and the diagonal reverse to the side is formed like the diagonal to the face; but its execution will be on the line 5.4 of the same figure. The formation of the cut and reverse to the thigh 4, E: and 3, F is the same as explained previously. But the execution will be done by lowering the arm to the corresponding lines. The same warning applies with respect to the execution on lines F, I, and E, 2, compared with the others.

Half Cut and Half Reverse

62. If from the common guard, the enemy adds their saber to your outside line, subjecting with their strong the weak of their opponent’s so much that its tip goes beyond their right vertical and lower than the shoulders, uncovering the high line, in consequence, as the one who is subjected you will turn your hand to Third, bending the arm to put your guard close to your left shoulder and at its height; and from here you will pass your sabre over that of your enemy, and extending your arm with vigor direct a horizontal cutting wound to their neck, this is called a half-reverse. If the engagement is in the inside with the same subjection, turn the hand to Fourth and bend the arm to join the guard to the right shoulder, direct, over the enemy’s sword a horizontal cutting wound to the neck, extending the arm vigorously, and there will be executed the half-cut.

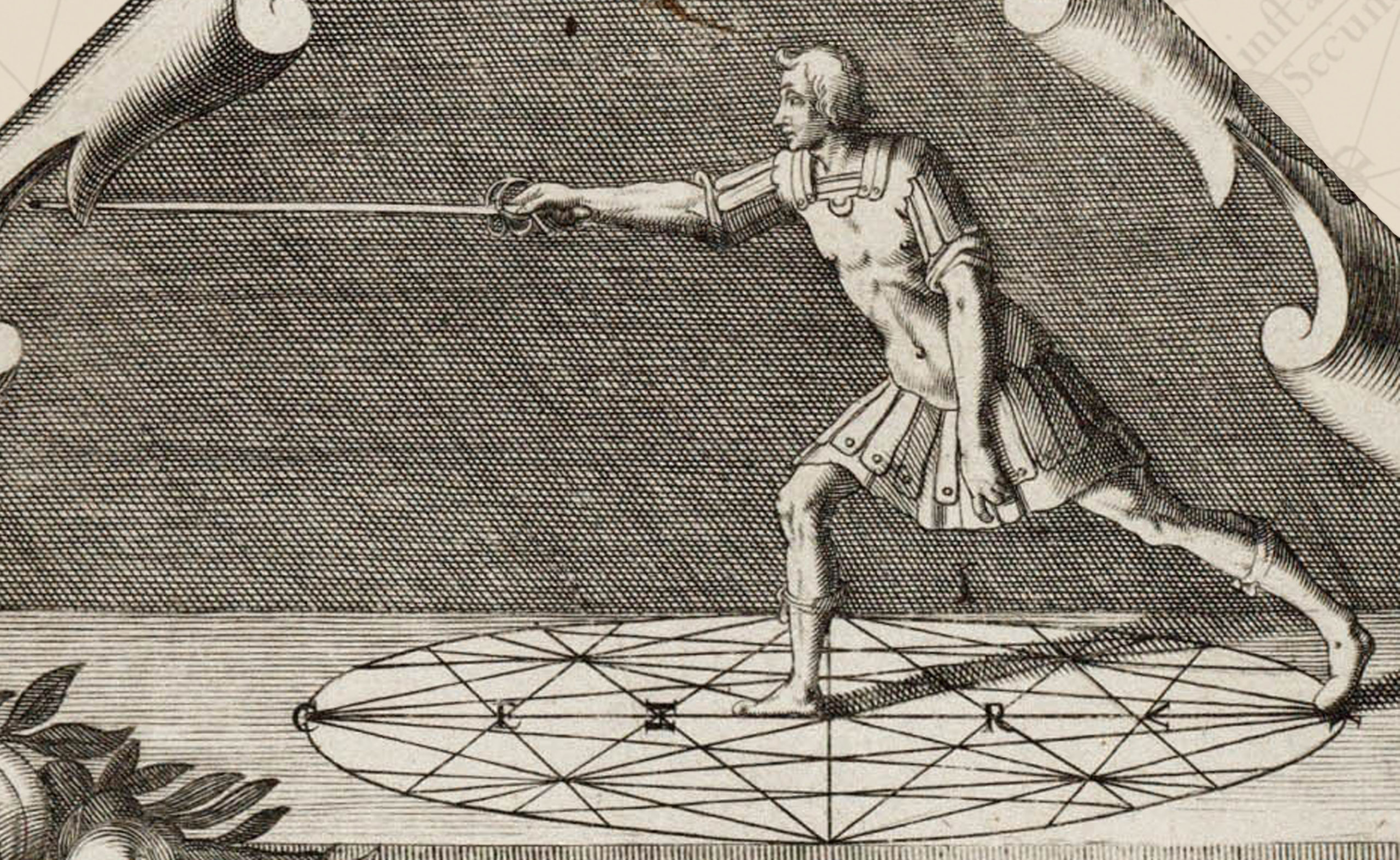

Free Thrust of Fourth

63. All the cuts and reverses explained to here have been have been seen to be formed by the point of the sabre. The attacks that follow are formed below or above the guard. For example: assume the offensive stance and the common guard (§ 51), if the opponent engages his sword on the outside having assumed the defensive stance (§ 52), free or pass the point underneath to the inside and pass it to the height you had before, turn your hand to Fourth and direct a thrust to their right side above the breast leaving our hand a little bit higher than the superior plane and covering the left vertical with the guard. This wound is called the free thrust of fourth.

Free Thrust of Third

64. Assume the offensive stance and the common guard, if the enemy engages their sword to the inside to wait, free or pass the point below to the outside, turn the hand fully to third position, raising it to the height said in the previous attack, and covering the right vertical with the guard, extend well the arm, direct the point to the shoulder of your opponent; this is called free thrust of third.

Thrust of Second

65. Positioned in the common guard and the corresponding stance, if the one who waits lowers the point of their sabre, and turning the hand in third, takes the weak of the other with their strong on the low inside and, moving the tip of their weapon away from the enemy’s right vertical and to the height of the middle plain, raising their guard to the supreme plane, forming the guard of sixth, uncovering the low outside. In consequence, the one who attacks, freeing above their guard with the hand in third, will direct the point to the right breast, with this, forming the thrust of second.

Thrust of First

66. Assuming the guard and stance s stated, the one who waits will walk the point of their sabre to the right of their enemy above the guard using only the wrist, set their strong on the weak of the other, and lowering the point on the same right side, they will make it circle under the other weapon until it is removed outside of their contrary’s left vertical and to the height of the middle plane, turning the hand at the same time fully into third position and raising it to the height of the supreme plane in the line of the right vertical, fighting out from the contrary weapon, forming with this operation the guard of fifth, with which is uncovered the inside line for the enemy to free around the guard, turning the hand fully to fourth, directing their point to the right breast and forming the thrust of first.

Concerning Oppositions

67. All attacks require the necessary formation, execution, and opposition. The first two were explained in the previous paragraphs (§ 56). Without what I call opposition to a posture, you cannot remove or parry safely, or have the necessary protection in attacking. Opposition is divided into that of the arm, hand, weapon, body, and planes, each of which needs to be present because, otherwise, you might undertake a practice of many years to be able to defend against any quarrel, but it will not be constant or free from very harmful errors. In consideration of this, I will expand a little in order to form a clear idea in the paragraphs that follow.

Opposition of the Arm

68. Opposition of the arm is that by which we are able to cover those attacks against which the guard cannot sufficiently defend. For example, cuts directed to any of the diagonals of the face may not be removed if the arm does not lead the hand to shoulder height. A thrust directed at the breast would hardly be removed if the hand was not brought up to the middle plane. It is, therefore, necessary that, when the point of the weapon occupies a plane, the arm occupies the one it must.

Opposition of the Hand

69. Opposition of the hand is the name given to movements which favor the disposition of the arm for its defense or offending your contrary. For example, a diagonal cut to the face may not be removed even when the arm and guard are in place, if the hand is in third. You will not be able to remove an inside thrust to the chest if the hand does not go to fourth, even though it and the arm occupy the corresponding place. In the offense, the same circumstances are necessary. For example, a cut thrown to the inside, if the hand is not turned to fourth, will not be able to cut to the place it is intended, nor will it give security to the one that throws it.

Opposition of the Weapon

70. Opposition of the weapon is the direction that must be taking for its point to occupy the plane and the place that the position of the arm and hand require. For example, a cut thrown to the flank will be achieved by the one who throws it if the point of the enemy’s sword is not taken out by the necessary amount in the removal, even if it is accompanied by the corresponding movement of the arm and hand. A thrust to the chest will not be removed if the parry does not occupy the point and plain corresponding to the point of the sabre.

Opposition of the Body

71. Opposition of the body is the name given to the distance that is taken in retiring or advancing by the line or its force. The object of these elements is the conservation of the individual. But as this is not limited to the defensive aspects, but many times is indispensable to the offense, oppositions take place in one case or another, the truth of which I will give sufficient evidence in the subsequent doctrines.

72. Suppose that the contrary throws a thrust or cut advancing or stepping deeply, and the parry is done with fixed feet. Immediately, he conceives to throw a series of attacks by virtue of the current disposition. But, take a retreat at the offense and it puts him in need to think of new things. This demonstrates the opposition of the body against premeditated offenses. Suppose that this offense was not made with the indicated remove but, at the time it was recognized the withdrawal was undertaken and you will see that this opposition was enough to frustrate not only this offense, but the ones that follow. More, if the above mentioned offense was accompanied with an advance, you would be able to conclude the one who did it, or do any of the operations that this opposition of the body provides, which I will treat in its place.

Opposition of the Planes

73. Equally as necessary as all of the above mentioned oppositions is that of the planes. This consists of making attacks always oppose the planes of greater strength to those of greater reach and those of greater reach to those of greater strength. For example, you cannot throw a thrust or cut to the inside with the necessary security if the movement of profile is not added to all of the other oppositions, even as the square is added to all attacks on the outside. In the first example, the offense with the point has the space from the right collateral to the left vertical, which are those of greater strength, for this reason int is indispensable to oppose with the greatest reach, the movement of profile. If the attack had taken with the point, the planes that exist from the collateral to the right vertical, it would have required the movement to square by the rule given.

74. The one who removes by opposing the contrary’s planes has to always agree on them with their opponent. I have already said that to throw a thrust or cut to the inside is done with the motion of profile and, when you attack to the outside, with the square. Then, to invade the planes of greater force, oppose with those of greater reach, and to the contrary. Then, from here, take it as a rule that when the enemy attacks to the inside, opposing with the planes of greater reach, that is to say to profile, you will remove by opposing also the planes of greater reach, or profile and to offenses attempted to the outside, with the square. This rule has the exception of always removing to the square when concluding the enemy, or for blows of the hand which you want to execute. Then, neither of these two operations will have good effect without putting up the planes of greater force against the enemy, whatever the attack.

75. Always have the greatest determination not to omit any of the principles in these important rules because, having contracted a habit of forgetting them, you will never become skilled. Nor would I dare go out as a guarantor of your success in the performance of important encounters.